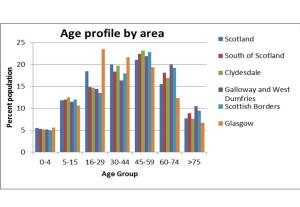

The South of Scotland is big, beautiful and it’s dying, or at least it’s age profile suggests that it’s heading that way.

Borderlands – Our Future a report on issues facing the South of Scotland (defined as the UK parliamentary constituencies of Dumfries and Galloway; Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale and Berwickshire, Roxburgh and Selkirk) published this week by the Westminster Scottish Affairs Committee highlights some of the issues: an ageing population, poorly paid jobs and poor infrastructure. It examines the problems facing the region, and comes up with some solutions which go in the right direction, but don’t seem to provide the step changes to which are really needed to revitalise the region.

Compared to the Scotland overall the population in the South of Scotland is older, and in particular there is a dearth of people aged 16 – 44 while over a quarter of the population are over 60. This is the opposite of cities like Edinburgh and Glasgow where proportions of the population are in their twenties and thirties. Sustainable communities need to have reasonably balanced populations, and the demographics of the South of Scotland, and rural Scotland in general are becoming unsustainable. In Galloway and West Dumfries just over half of the population is of working age compared to 60 % in Scotland as a whole and 65 % in Glasgow. The problem isn’t that there are too many older people in rural areas, its that there are too few young ones.

Policies to address this tend to focus on creating more jobs and training in rural areas, without looking at why young people are leaving. Jobs are only part of the problem – for people in their teens and twenties social life is also important. Perhaps the nick-name for the region “Boredomlands” gives a clue – many young people there’s not much going on for them – sports and social facilities are limited; public transport is poor and more of less non-existent in the evenings – a night out means having a car and not driving. As friends move into cities to work or study those remaining become increasingly isolated.

In many cases young people leave the area to study before they start to look for jobs permanent jobs Once they’ve gone they don’t come back quickly. One of the things which could be game-changing in keeping young people in the South would be to create a University of the South of Scotland. This is idea was supported by the Scottish Borders Chamber of Commerce in their evidence to the Scottish Affairs Committee. We do have some higher education in the South of Scotland with an outpost of Heriot Watt University at Galashiels, a mixed bag of courses from the University of the West of Scotland, the Open University and an outpost of Glasgow University at the Crichton Campus in Dumfries, plus bits of Scotland’s Rural College around Dumfries, but in all cases these are minor outposts not full blown universities based in the region and focussed on it. They’re all pretty small, teaching a limited range of subjects and not attracting the critical mass of students needed to be able to offering the wider social and cultural life associated with city universities. What the South of Scotland needs is a proper university offering a full range of subjects, beyond the current offering of “things to do with sheep and farming”. Young people in the South have as much right to learn about culture, languages, science and engineering as anyone else! A good university in the South of Scotland could not only enable young people to stay in the region, but could attract students from elsewhere in Scotland, the UK and Europe.

Not only would a university for the South of Scotland help young people to stay in the area, it would bring high skilled, well paid work in teaching and research as well as a range of supporting jobs and potentially also spin off companies. Students who have studied in the area would be more likely to settle there and start businesses of their own.

Of course if young people are to attend a local university they need to be able to get to it! It is almost impossible to reach Dumfries or Gala by public transport in time for a normal working day from areas which might be expected to be in their catchment, although it is possible to get to Edinburgh and Glasgow. The Scottish Affairs Committee report recognises that public transport needs to be improved, but focusses it attention on extending the new Borders railway from Tweedbank on to Hawick and Carlisle. This is the sort of big, expensive infrastructure project which governments like, but while the proposal is welcome, it neglects the more fundamental need for local public transport. Without connecting bus services most residents can’t reach Gala, Tweedbank or Hawick without driving! The need for public transport brings us back to the ageing population. Pensioners are disproportionate users of public transport, perhaps because they have free access to it, perhaps because they can no longer drive for themselves of perhaps simply because they have more time. However for them to use public transport there must be frequent and accessible services for them to use.

Some of the other recommendations in the report are pretty obvious: employers everywhere should be paying a living wage and high speed broadband and mobile phone coverage are becoming increasing essential for individuals and business and should be rolled out in the South of Scotland as soon as possible. The need for better cross-border working with the north of England is highlighted, but there is no discussion of potential opportunities from improved links with Northern Ireland and the Republic which could benefit the southwest Scotland. Although the report is welcome as far as it goes, it is disappointing that rural housing, access to land and diversifying the economy are not touched on.

Housing is a particular problem, as high house prices couples with low wages price many people out of the communities which they grew up in. Planning rules to do not favour house building in rural areas, while the housing stock is increasingly bought up for use as second homes, holiday houses and by people retiring to the area. There is an urgent need for affordable and social housing to be built in rural areas and planning rules need to be rethought to allow this. Improving the right of communities to buy or control the land around them could help with this.

Agricultural, forestry and fishing activities inextricably linked with rural areas, but actually only employ about 4% of the workforce. The largest employers in the South of Scotland are the retail sector and healthcare and social services. Manufacturing supports a surprisingly high proportion of the population – at nearly 9 % this is more than in Glasgow. It is not clear from Scottish Government data what this includes, but traditional industries such as textiles and food process will fall into this as well as some agricultural engineering. A better understanding of what this manufacturing involves could enable it to be supported better.

The South of Scotland and its people have enormous potential, but our young people are our future – we cannot afford to lose them!

References

Data on age distribution and industry profiles taken from the 2011 census http://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/ods-web/area.html